He is known as Eversiempre for the simple, random fact that when he created his Instagram account, “Ever”, his actual artistic name, was already taken. Nicolás Romero (Buenos Aires, 1985) started twenty years ago now, signing and doing graffiti throw ups in the streets of his native Buenos Aires, a city experiencing the hangover of an 8-year military dictatorship and where, by that time, Street Art was understood as an expression of freedom against the dark times and censorship.

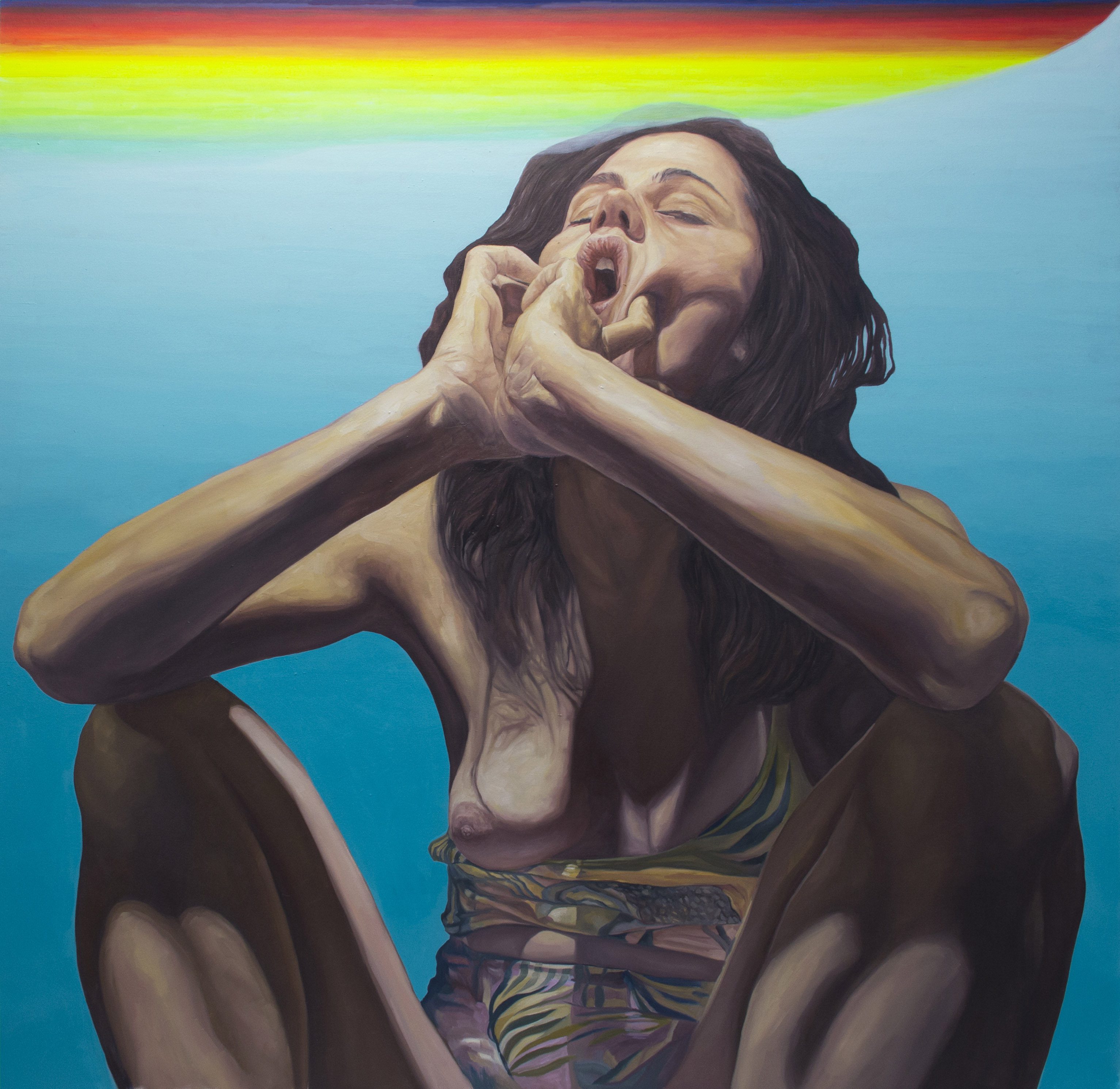

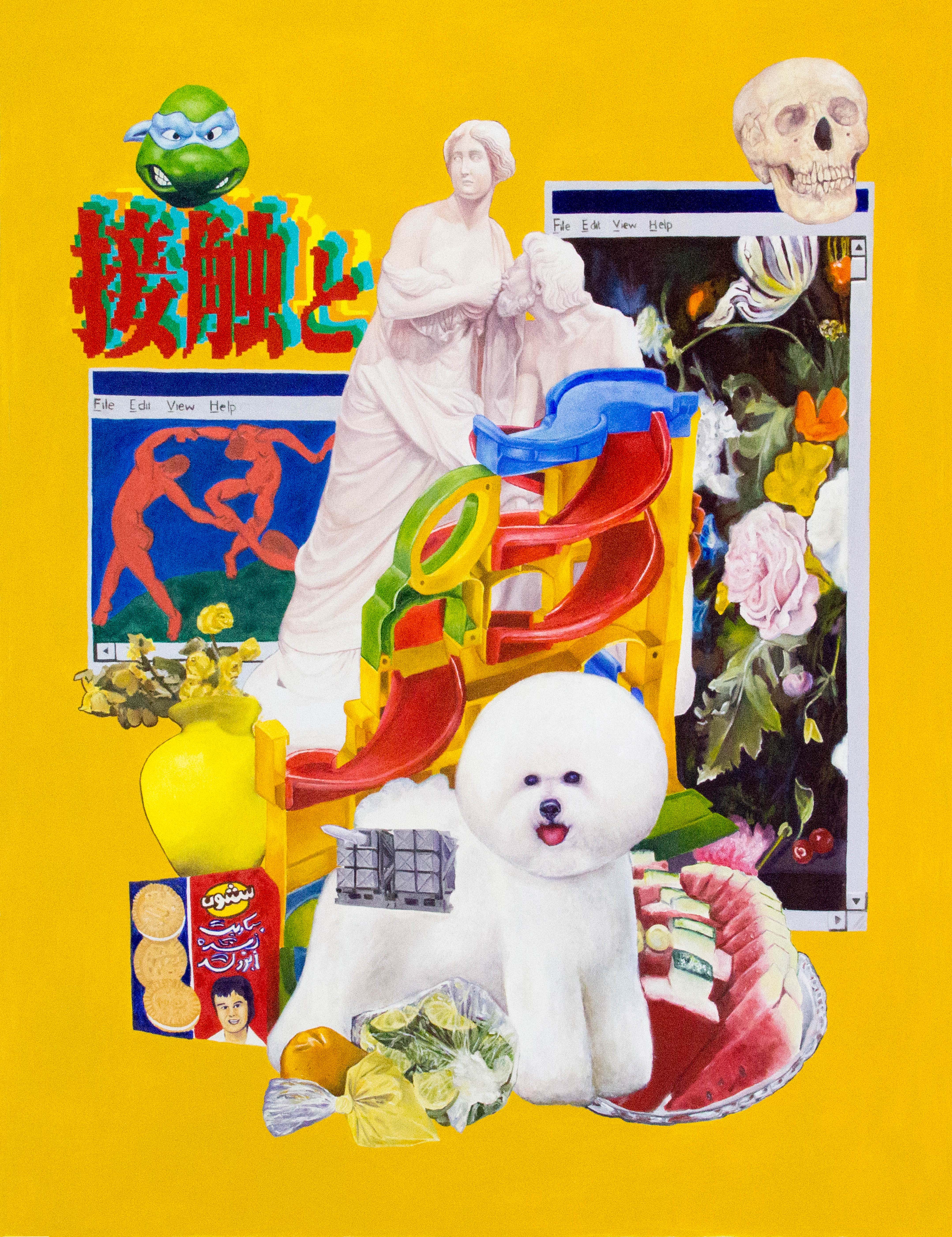

He left graffiti aside to give a complete turnaround and started drawing faces, mostly of political figures with whom he experimented and played with their political burden in the street, and from whom emanated streams of life and color, while his studio work was taking the shape of flesh and feminine and masculine bodies. “Still Life”, the last series he has been working on for the past years, Nicolás found a new way to use the image as a social reflection. «I realized that through objects and symbols I’m able to say much more», he says. Kittens, poodles, drones, eggplants, figs, flowers, classic artworks, contemporary icons and other elements he finds in the immediate territory where the mural intervention is taking place are intermingled in his chaotic and surreal still life.

Last February, we shared a week with him in Madrid with loads of art, many liters of plastic paint and a few beers in between, while he was painting 18-meter-high mural in Calle Embajadores for the WALLS Program curated by Urvanity Arts. Quarantine has caught him in Barcelona while participating in the artistic residency by Adidas “Change is a Team Sport” so we took the chance to talk review with him his work, his references and methodologies. Lots of sense of humor, content and a conscious footprint, just like in his artwork.

We were with you in Madrid at the end of February for the realization of your last mural project. Kittens, ancient objects taken from Madrid’s flea market El Rastro, Matisse’s dance… Before your arrival we had several conversations because you wanted to get to know as much as you could about the neighborhood where it was located. Who lives there, how is this community, the restaurants we could find there…

I always try to investigate the place where I’m going to paint before I go and if I have the chance and the time I try to visit it before doing so. I want to work with the objects that are around that wall. When I arrived to Madrid and started this wall, all the information I asked for about the neighborhood was actually there. The different communities of different nationalities, the curry smell, the barbershops… At first I wasn’t sure if the reception would be good or not, but it would definitely be very straightforward. When I was at the lifting platform painting 5 stories high, I constantly had people passing by and yelling like «Hey! What’s it about? And aren’t you going to paint this or that? And what is that fig?». I liked discovering that in Lavapiés there is a very large community concerned about what may happen in their neighborhood, both in its present and its future. When you realize the way the community where you are working is attentive to this transformation is when you also worry more about how to work from that space.

How did this wall came up?

From this sense of community situation, Matisse’s painting of the dancers came to mind: people dancing in the same place and holding hands. That was my starting point. Then I worked with other elements that could refer to the famous flea market of El Rastro. The cats was just a coincidence, I didn’t know the people from Madrid were called ‘gatos’ (cats in Spanish). It always happens that when you work in important cities, capital cities like Madrid, you have to go through certain filters. Public Art does also have this patronizing part when painting such a large wall and having so much into the logistical level. You have to deal with factors and people who guide you. When I was younger I wanted to paint whatever I wanted to, but in the end, when I generate a work, which is a search for symbols of a space, I have to agree with certain individuals and local entities on the meaning of those elements. A Coca-Cola bottle painted on a wall in Mexico is not the same as in Africa. Or what the fig represents in Spain or in the United States. What constitutes the mural process is a mixture between what I put on my side and that filter that I need to delegate. In the end what I’m trying to do is research into that space, see what that place symbolizes.

At the end of the day you leave your trace through murals wherever you go, I guess it’s important to you to do it as a conscious footprint…

From the moment this ‘Street Art’ movement was gestating, going from festival to festival painting, I realized that I was doing what I wanted but at the end of the day I would leave that place and what was left was the trace of myself and my ego. Just me saying something. I would leave without acquiring any experience of those spaces. It is now through this line of investigation of the places that I go to paint that I’ve found a way to connect with the place. There are wonderful things that just happen naturally. We are in a consumerist system in which the way we buy represents ourselves. We make ourselves be understood as individual and free beings through buying things that have their political or ethical background. It was when I realized that through objects and symbols I could say much more. We find ourselves at a time where we’re rethinking identity systems of sexual classifications and it seemed to me that if I kept painting human figures, as I had been doing until that moment, I continued to collaborate with the old system. I also had to adapt myself to the new context and try to see how I could work from a new platform.

Does your studio work differ much from the mural one?

My studio work it’s more self-referential. I work from the other side: the things that I consume, the things that I like, the things I hate, the ones that remind me of someone or a situation. It’s more personal. Public art is a very powerful tool but at the same time I ask myself: Do I want open up to this situation? Let people judge me? In my studio work I have that opportunity of dialogue with myself. I personally have an inability to approach things in a natural way, under established communication patterns. To get emotionally close to something or someone I have to paint it, that’s the only way I found.

In which way your roots into graffiti glimpse in your current work?

I had a moment when I wanted to get away from graffiti, the system seemed somewhat closed to me and I realized that unconsciously my graffiti side developed in the way I work with colors. The colored backgrounds that I paint in my works, the fixation in the colors being combined with the rest of the objects. That comes from when I made letters and throw ups, they were visual situations. First I combine the elements and then I think about the background color.

Let’s go back in time then to your beginnings in graffiti…

I started painting in the street when I was 16 years old out of curiosity. I remember seeing these signatures in the school bathrooms, I found them very interesting to decipher, it was something else. I got in contact with the guys who did that were doing them and from there it was just putting things in common. Something really positive that graffiti has beyond the artistic search is the connection through friendship. At the time I was looking for something completely out of the patterns from which I was trying to communicate my work. I did not even consider it ‘artwork’, it was rather thinking “I want to draw, how can I do it and how can I call people’s attention with my drawings”. I had been drawing for several years, I had some knowledge of painting, but graffiti made me take it up in a new space that felt comfortable. At the same time we absorbed a different type of culture such as hip hop, breakdance, skate… I was only missing my Eminem hat! Actually everything goes together, I was involved in skate and as a consequence I ended up involved in graffiti. I got together with a crew that was drinking from other groups, we were all teaching each other…

How do you start making a name out of Ever in the Argentinian scene?

In 2002 I started painting in the streets with Brujo, a neighbor of mine that had been doing some street for a few years. Through him I got to meet the people of one of the first graffiti crews in Argentina, DSR, and by default I started going out with them. Franco Fasoli who signed as JAZ was there and others like Poeta, Mart, Dano … The movement began to grow and the demand for this type of work did too. There was a Hip Hop club where everyone who painted used to meet on Saturdays, from those who painted trains to murals… We were more like in the ‘softies’ side. I did very little vandalism, I didn’t paint blinds or did any bombing, it generated me a lot of stress. I was into mural graffiti, we made letters but we had more time to create the, and at the same time I was like “Why would I do it illegally and quickly when in Buenos Aires nobody will tell you anything if you were painting in the street?”. Then I realized that I was really bad with bubbles and letters so I started to think what I could bring to the group in a visual way. That’s when I started making faces. I liked it, I felt it complicated but I thought I could do something with it.

What relationship did the country have with that era of the beginnings of graffiti?

In those early years, art represented a manifestation of freedom in Argentina. After the events of the 70s and early 80s, in which there was a strong repression by the military governments and in which people who thought differently would “disappear”, this feeling of going out into the streets was accentuated. This helped in making the graffiti scene in Argentina less prone to being repressed, painting was seen as an activity of freedom. In Argentina people are more concerned about knowing why you do it and who pays you than wondering if it is legal or not. In Buenos Aires in particular, that constant to occupy spaces naturally began to occur, either through demonstrations with people on the streets or artistically speaking. It is a city that gives you the possibility to experiment, the pedestrian is a very participative person, they always want to talk to you and intervene in what you are doing, he is extremely curious and the results when you paint are immediate.

What were your influences at the time?

A lot of people used to come from Europe to Buenos Aires. We got together to see European graffiti books and magazines. Somehow this politically and economically colonial relationship between Argentina, mostly Latin America, with Europe meant that what we consumed was European graffiti and hip hop, which at the same time was drinking from the American. Sometimes we weren’t able to understand what people form Europe were doing: we were trying to do good letterings and in Europe they were making lines, shapes… As we progressed we understood the way the street artwork was carried out in Europe, it went beyond letters.

How does your work and career evolve to make the leap to a more professional environment?

By the early 2000s I had an alternative job in marketing, none of us lived out of painting. But the wheel began to move and more jobs and commissions began to be generated. I started and so I jumped into the swimming pool. Luckily everything went well. Between 2009-2010 I started to be invited to projects outside Argentina and that is when a Street Art circuit began to be generated worldwide. Moving and traveling changed my job a lot, the boost was totally different. Before that perior, my work in Argentina was more political, I had a more demanding gesture, the one of living in a city where there was always something to say or an unsatisfied situation. When these projects begin to be generated outside my country, it is when I took perspective of the place where I lived.

In your work still remains a strong political gesture, maybe less apparent.

I believe that every action applied in the public space, where people passes by and that in somehow communicates with them, is going to be political. You are modifying something that already exists. I see a very clear example in buildings. They represent a symbol of power: the building of a major company is large, tall and has the company’s sing name on top. That, I consider a graffiti, only with much more money. Is the same concept than in graffiti, you just want to have your name on top. If powerful companies or institutions symbolize their power through these structures that are inhabited by people, then the only thing people have left is the feeling that the street belongs to them. I don’t know if there’s anyone in this profession who thinks that they are not doing a political action when painting in the street, the act of painting itself is political.

In addition to elements that you find while investigating the space, as we were saying at the beginning, your walls are highly influenced by those elements that today shape the contemporary identity, Internet, memes, kittens … What is the your criterion when combining the image?

The amount of information that we consume every day is affecting our criteria. Unfortunately we are no longer impressed by many things. By combining memes or images with different values or objects such as drones, fighter jets … what I try to discuss is that today basically everything means the same for us. It is what I like about mixing elements that we first believe they have nothing in common but that are nevertheless at the same level. For example, when I combine Trump with a cat it’s because if you look at the number of times Trump is mentioned on the Internet it’s almost the same number of times as when people search for cats. It’s crazy numbers! They are two antagonistic elements but if you dig they have many things in common. The meme is a manipulation of the image, it’s taking an image out of context and changing it to another type of situation, I do the same.

What is the purpose of your work in public space?

I think there is always an idealism in the artist to try to modify something for the viewer. When I paint in public space I ask myself who is my ideal observer, who do I paint for? Modifying people’s sensory space and transferring that passionate subjectivity is what motivates me. So I use various visual resources and different information criteria. Part of what I want is to confuse people and I realized that I like to camouflage myself in various messages and have them reinterpret them. For me the mural begins to work after the artist finishes and abandons that work. The act of painting it is a completely logistical matter.

And what does Nico do when he doesn’t paint?

I try to read, and I say ‘try’ because we are currently always ‘trying’. I like going to museums a lot, I love them. I’m very social, I like to go out with friends, I have colleagues with whom I only talk about art and with others with whom we go out to drink and I don’t talk about art. I like that. In Buenos Aires you will always find me in the same six places, ordering the same as always. That feeling of freedom is what I enjoy the most.

You have been in Barcelona for almost two months in the artistic residence of Adidas ‘Change is a Team Sport’ curated by B-murals and Urvanity, do you miss Buenos Aires?

Not so much … I have the feeling that if the people who are in Argentina are fine, I am fine. My house is much smaller than the space I am now and I couldn’t set up a studio there, I have too many things and I don’t have a wall to paint. I’m fine here and I like new stimuli that I’m getting. If I was in my house I would probably be watching Netflix…