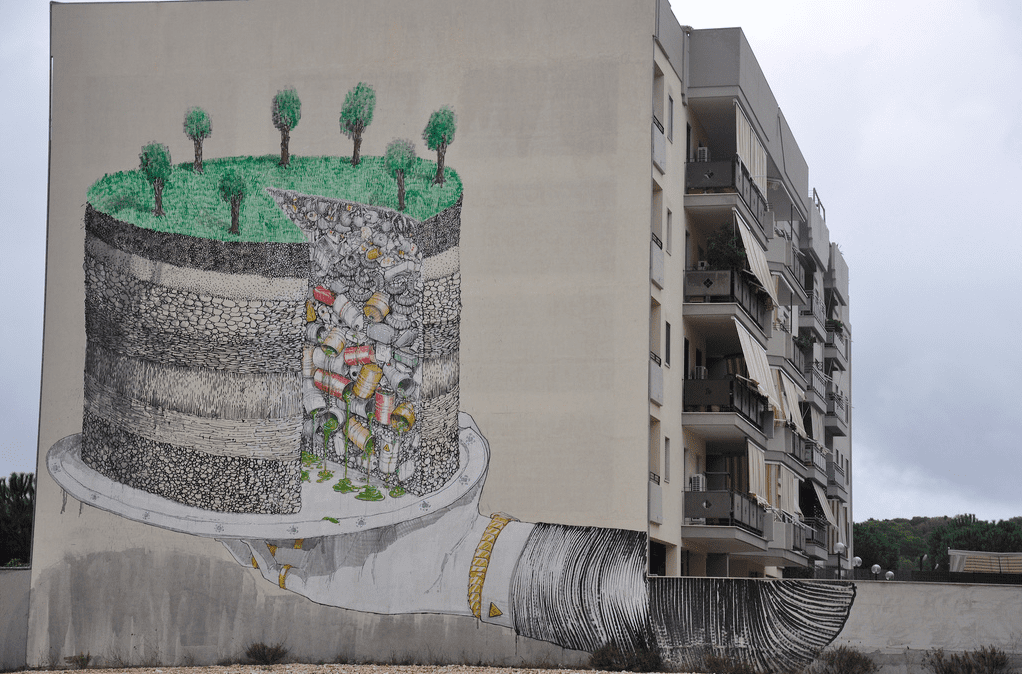

He’s into punk music, the underground scene and he’s about doing things without asking too many questions. Angelo Milano doesn’t want to like, but rather to do things that he likes. In 2008 he started in Grottaglie, a small town in the interior of the Italian Puglia, the first edition of FAME, the first self-financed and illegal Street Art festival with a line-up that brought together names like Conor Harrington, Blu, JR or Lucy Mclauchlan, and in the five years that followed would be joined by others like Swoon, Escif, Boris Hoppek, Momo, Sam3, Os Gemeos or Vhils.

Without any external funding and almost without knowing it, Angelo Milano was organizing in the South of Italy one of the most important festivals and pioneer of the urban scene at an international level, together with artists who shared the same life philosophy and an urge to express themselves through art. With Studio Cromie, his handmade printing studio, he paid himself for the festival by selling artists limited silkscreens editions that he produced there, while his father took care of moving the artists and his mother made sure that they did not miss a plate of hot pasta on the table. Five years of success, spectacular murals and above all a freedom rarely experienced, were enough for him to finish the project. He had already said everything he needed to say.

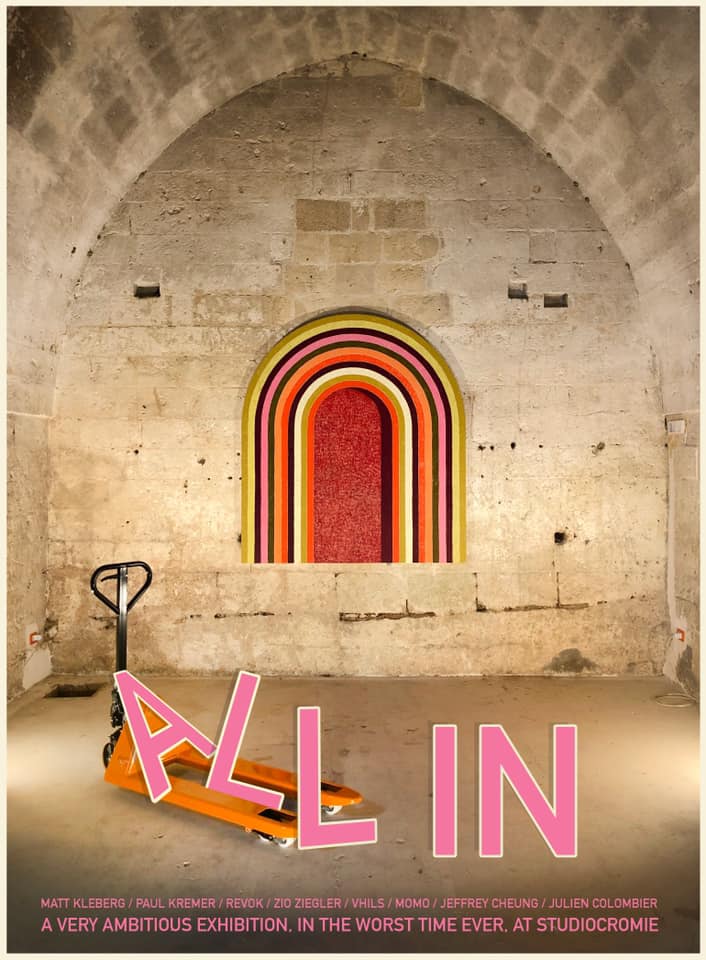

A few years later, Studio Cromie’s workshop was joined by a huge stone space converted into a gallery that today hosts events and exhibitions of number one artists and is about to open ALL IN, his latest and most ambitious exhibition, a personal commitment and an evolution presenting work by Paul Kremer, Revok, Momo, Matt Kleberg, Julien Colombier and Vhils among others. We talk to Angelo Milano about his past and his present and we do it without any filters.

Studio Cromie gallery space in Grottaglie

How was FAME, one of the world’s pioneering urban art festivals in Grottaglie City, born in 2008? What was your motivation?

In this area of southern Italy there is nothing going on, nothing happens here, it’s a desert. On one hand I would say it was boredom and on the other hand it was resources, because that same fact of nothingness is what allows me to do whatever I want. No one is prepared for anything that might happen, and with FAME that’s exactly what happened. I started organizing it without asking for any permission, without any funding… It came out instinctively and it wasn’t until later we discovered the consequences. I was never interested in the reality of places where hundreds of things are already happening and you are just a passive observer. I have always been very active and when you work from nothing you have much more freedom.

Lucy Mclauchlan

Blu

Conor Harrington

Already the first year of the festival is attended by number one artists such as Conor Harrington, Blu, Ethos, JR, Lucy Mclauchlan, Erica Il Cane… How does this get started and get to know each other?

I met all of them here in Grotagglie through a punk music festival that I organized when I was almost a kid. It was a very DIY thing, and many of these artists came because we all enjoyed punk music. By that time in Italy there was a lot of underground cultural activity going on at squats, it was a way of communicating ourselves very far from the mainstream. Some of them played music, others painted, others did graffiti… But everyone was doing things just because we felt them from deep inside, nobody saw it as a job, it was all very natural, we acted urgently. I always understood that by doing things I was going to build bridges.

In fact, the festival had a very punk spirit, provocative and above all a very clear message that the public space belongs to everyone?

More than a specific spirit, it was very much in line with my emotions and feelings about art, about community and public space. It was a very selfish expression and one that was hooked on my needs. I understood it as something I wanted to enjoy myself and it just happened to take on a public dimension. I wanted to meet interesting people and because of my, let’s say, extreme tastes, things began to take on a provocative dimension. It was not my intention to please everyone. For me to enjoy it, it had to be extreme.

Aec Interesnikazki

Vhils

Slinkachu

Blu

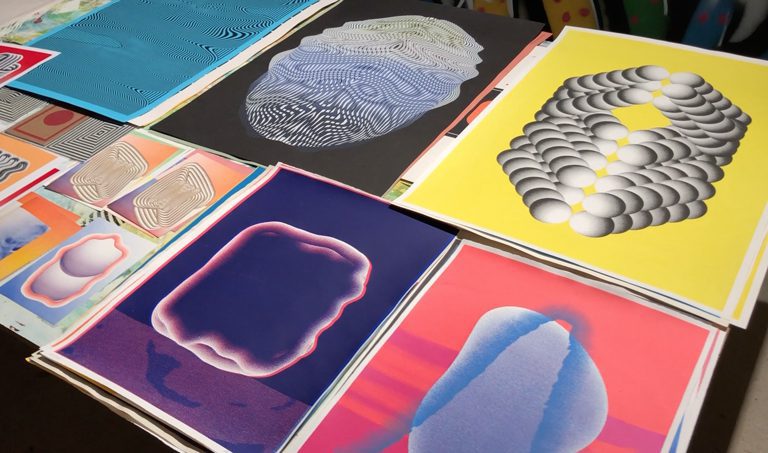

The festival lasted five years but you never went on looking for any kind of external funding. How did you manage to finance such a festival? What role does Studio Cromie play in this?

I was a graphic designer and designed covers for music albums, but I never liked the final printing of my work. So I decided to set up my own workshop to print it myself and learn the techniques. So the moment I started meeting artists I decided to start printing their designs and this helped me to finance the festival. I would invite artists and we would work together producing their stuff, selling it. It gave me the money I needed to cover all the expenses of the festival. I neither had nor wanted any public subsidies, because that meant I would have to please the rest. Doing it alone made me feel free, it was a big expense and a big bet every year, but luckily it went good every year.

Studio Cromie printing studio

How were those five years of the festival? Did you encounter many obstacles?

At first it was crazy, nobody understood what we were doing. People would stop us while painting and ask all kinds of questions. Basically it was: “Do you have authorization? Who pays for this? Who won last year?…” As if it was all part of a competition. No one could understand that it was something that was done for the sake of doing it, there was a need to communicate freely. The institutions didn’t understand anything either so they tried to stop us. They started to erase some of the paintings we were doing but it was quite unproductive for them, since I would post it on the Internet and people all over Italy started to complain. The City Council and the police ended up with their hands tied because whatever they did people would position themselves against.

Erica Il Cane

Sam3

Lucy Mclauchlan

What were you looking for with this festival?

I wanted total freedom of expression, to be able to do anything. When the authorities stopped being on top of us it actually bothered me because I liked to have an opposing or at least critical speaker on the other side. From the moment everyone outside Grottaglie started to speak well about us, we lost it. The citizen of Grotagglie went with the flow: when they heard how positive it was to have a festival like this, they stopped questioning and approved anything we did. That’s the year we decided to boycott it by painting a few penises in the street: we wanted to see if anyone was still awake, we wanted to be stopped, to have our work questioned and that didn’t happen. I got really bored.

And after five years of FAME and in one of its best leading moments, where artists such as Momo, Sam3, Os Gemeos, Escif, Swoon, Boris Hoppek, Brad Downey, Vhils or Nespoon had participated… You decide to end it all.

Yes, I was ready for it. I think everything has its moment and it wasn’t useful for me to keep doing something where I already said everything I had to say. The festival could have been carried out many more years, it was going to be very comfortable for me financially because all the sales started to work very well by then, but I wouldn’t have enjoyed it.

Cyop & Kaf

Boris Hoppek

Os Gemeos

Were you aware that with this festival, celebrated between 2008 and 2012, you were being one of the pioneers of a whole movement of Street Art festivals?

It was obvious because this was the first one, but it bothered me a lot to see the others that were starting. Just here, in this southern region of Italy, there were several who tried to do the same thing I was doing with the City Hall, with the politician on duty by their hand, with permits… There was no longer such urgency from which FAME emerged. Any comparison always bothered me because from the outside you only see the photos on the Internet and with no documentation they are going to look similar. What we were doing here had nothing to do with a photo, it was a much more powerful form of communication. To tell you the truth, the murals themselves never really interested me, but at that time it was a very strong way to communicate. If I had been told that something else was as strong weapon to communicate as painting a wall was, I would have done it. Seeing these replicas was another reason for me to stop, I didn’t like to think that what we were doing could be part of a model.

Brad Downey

Momo

Escif

Aryz

Is art that is supported by brands less legitimate? Does it lose essence when brands try to capitalize on it?

The truth is that at that time this artistic phenomenon was still very free, it didn’t have the interest of the big corporations, of the Contemporary Art system, or the brands. The artists were doing their art freely, without thinking about money or their professional careers, and that was what interested me, it was a very punk attitude. At that time you would said no to brands, collaborating with some of them would make you look a bit like a looser. Now it seems very cool and everyone is fine with it, it’s all more superficial. Selling our stuff without entering the ‘official’ art circuit was a real alternative to the system that prevails now.

What did you do to step away from this?

We made silkscreen prints in limited editions of one hundred copies and they came out at 100€. The sale of art was more democratic, everyone could have access to it and it was good to make a living of it. Then artists started making bigger original works, and it was still somewhat parallel to the art system. There was also this attitude of fuck everything else that was official, until that moment they hadn’t realized that we existed. From one moment to the next, like it happens to all cultural phenomena born in the underground, the system takes notice of you. When this happened, all the artists, one by one, became corrupted. We lost the freedom to do things to our liking, in our timings and with the freedom we had before. It’s tempting but it can be done differently. I know it for sure because I have friends who have done it with much more coherence and much more freedom than others. Now they are free, perhaps without money, but truly free.

Inside the gallery space with works by Cyop & Kaf

Works by Paul Kremer and Revok

Have you managed to continue working in the art world without falling into the mainstream?

I created my own island. I never communicate with people I don’t like, I don’t do projects with people I don’t like and I don’t sell artists I’m not interested in, just because they’re in vogue. I stopped doing events to the public, I don’t do Street Art festivals anymore but I invite the artists I like personally to come and collaborate with me for a month and then we sell the work we produce. I’m not against selling, I don’t hate making money, but it can be done consciously without having to suck up to anyone. I am still consistent with that look.

What artists cross your mind when you talk about coherence?

Now, for example, I’m working a lot with Paul Kremer, an exquisite person who began to make art at the age of 40. Also Cyop & Kaf, a duo from Naples that do a lot of social work without selling it later as propaganda. Or Akay from Sweden, a total idol, has a very simple and coherent look at what he does. I really enjoy meeting new people, but always in this independent way, without creating a structure. That’s why I work alone.

In all these years you have become a critical eye and artists catalyzer…

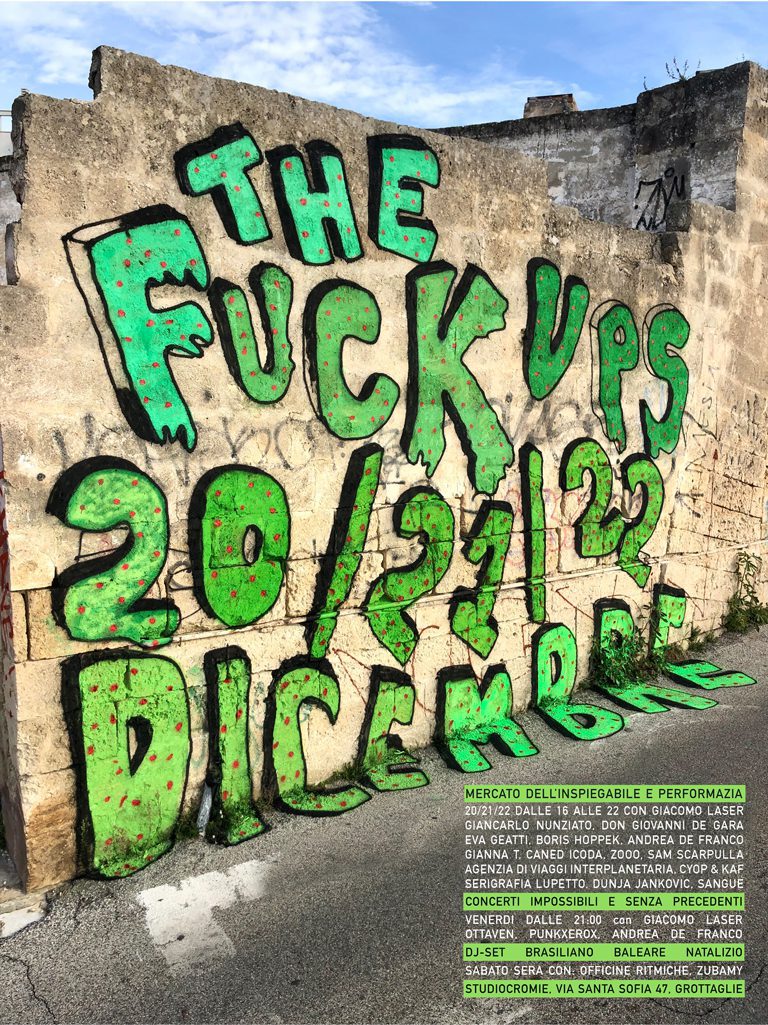

It was my mission for a long time, to discover unknown artists so that they could begin to be known and be able to live from their art. I believe very much in the quality of the people who work with me. Now with my gallery and space Studio Cromie I find myself at a point where I can continue to do so but not as I used to do before, because the Studio Cromie client apart from quality they expect a good investment, and by pulling artists out of thin air I can’t guarantee it. That’s why got involved in another very fun project that I celebrate twice a year called ‘The FuckUps’, where I bring artists that I like very much, perhaps more than Studio Cromie, but they are already ‘fucked’, let’s say they do not know how to sell or communicate their work… It’s my research space, much more sincere. I also am at Studio Cromie but I’m more concerned about the artists selling their pieces.

The FuckUps line up

Dunja Jankovic

You are about to open a large exhibition called “All In” at Studio Cromie, a big challenge.

In times of crisis I like to show my clients and artists that Studio Cromie is doing good, still strong and working hard so that they can have confidence in what I do. This exhibition has been a very big bet, a total challenge and an evolution of what I’m doing. I will present new original work by very powerful and well-known artists such as Paul Kremer, Revok, Matt Kleberg, Julien Colombier, Momo, Jeffrey Cheung… I can’t wait to open it, they are going to be giant works everywhere, beautiful all of them.

Also during confinement I did a lot of silkscreen printing in the workshop. Vhils, Braulio Amado, again Cheung… I was non-stop printing every day and will release them soon too. Not to close in dates, because if I make too much money one of a time I will have to pay too many taxes in Italy, and I hate paying them (laughs)!

“All In” exhibition

Revok installing of the artwork